The primary objective for the archeological project is to understand how the site's ceremonial core grew over time. Since Tiwanaku has been terribly damaged over the centuries, such understanding is very difficult to achieve. Substantial damage occurred to the site both during the Pre-Columbian period, when buildings were modified and torn down to make room for new ones, or by the Inca, and after them the European invasion and people of Bolivia, during which about 90 percent of the site's stone constructions were destroyed to build their structures. That is the reason why the buildings of Tiwanaku look unfinished. Nevertheless, archeologists have achieved an idea of how Tiwanaku's monumental city grew. What we know is based partly on nearly a century of excavations.

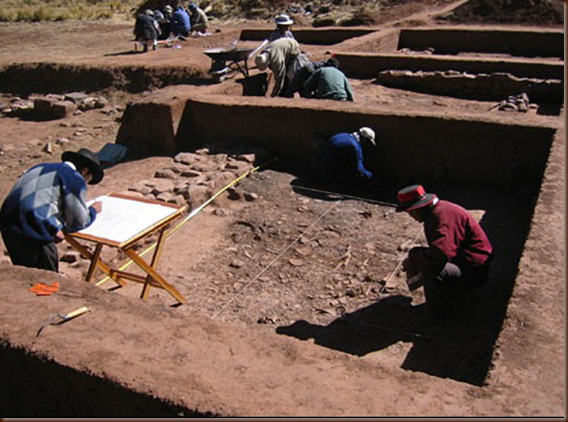

Excavation at Pumapunku pyramid refuse pit and feeding halls

Tiwanaku’s Earliest monuments

The earliest monuments that survive from the period of approximately 300 B.C. to A.D. 200 are the semi-subterranean temple (background) and the Chunchukala Complex (foreground).

Tiwanaku - Semi-subterranean Temple walls

Most certainly there had been other ritual buildings that were long ago dismantled by the people of Tiwanaku themselves or buried under subsequent constructions and by those who came after them At this stage in time, Tiwanaku was probably an important local ceremonial site competing with other ceremonial sites in the Titicaca basin. The faces on the walls are called Tenon heads and are blocks of stone with carved heads on them. They represent either important leaders or the ancestors of the people of Tiwanaku.

Starting in about 200 A.D., they began construction on the Kalasasaya complex by building the Subterranean Temple first. After that the Kalasasaya Complex pillars were erected to serve as a solar observatory. The walls pictured below of the Kalasasaya, are almost all reconstruction. The original stones making up the Kalasasaya would have resembled a more "Stonehenge" like style, spaced evenly apart and standing straight up.

Tiwanaku- Modern walls of the Kalasasaya Complex (note the original pillars in the wall).

Unfortunately, the parties that made the reconstructions decided to enclose the Kalasasaya Complex with a wall that they themselves built. Ironically enough, the reconstruction itself is actually much poorer quality stonework than the people of Tiwanaku would do. It should also be noted that the Gateway of the Sun that now stands in the Kalasasaya Complex is not in its original location, having been moved sometime earlier from its original location.

The Kalasasaya Complex Solar Observatory as it should look

The original Kalasasaya Temple being an astronomical observatory may have looked more like this. A common source of data for archaeoastronomy is the study of alignments. This is based on the assumption that the axis of alignment of an archaeological site is meaningfully oriented towards an astronomical target. A common justification for the need for astronomical observatory is the need to develop an accurate calendar for agricultural purposes.

The Kalasasaya Complex was used as a ceremonial center and for astronomical observations, allowing users to observe and define certain astronomical activities on any date of the 365-day year. On the spring and fall equinoxes (21 March and 21 September, respectively, for the southern hemisphere) the light of Sun shined through the main entrance gate. This indicates that the Tiwanaku civilization understood earth/sun cycles (a calendar) and astronomy well enough to incorporate them into their construction projects and activities The importance of zenith passages was very important to the people of the ancient world. For peoples living between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn there are two days of the year when the noon Sun passes directly overhead and casts no shadow. In parts of Mesoamerica this was considered a significant day as it would herald the arrival of rains, and so play a part in the cycle of agriculture.

Stars in alignment above Tiwanaku

Another motive for studying the sky is to understand and explain the universe. In these cultures, myth was a tool for achieving this and the explanations for life, while not reflecting the standards of modern science; these were cosmologies that became a part of their religion and their understanding of their world.

No comments:

Post a Comment